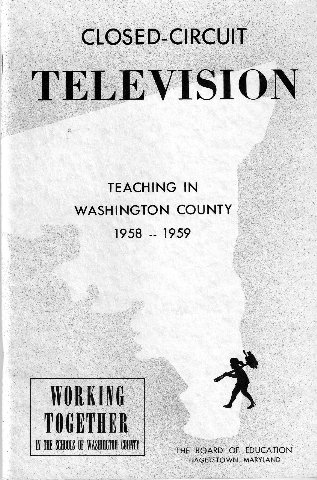

WASHINGTON

COUNTY CLOSED CIRCUIT TELEVISION REPORT - 1963

NOTE:

This

publication was produced by the School System. – A very informative

Historical, six-year article.

The

Board of Education first considered using television in the schools in 1954.

The Board was then aware that the children of the 1950's came to school with a

better background of information than earlier generations-and that a primary

reason for this was exposure to new experiences via television in the home. This

situation suggested a need for curriculum changes to avoid trying to teach

children things they already knew. It also suggested that television might be

even more valuable in the classroom than in the living room.

The

Board of Education first considered using television in the schools in 1954.

The Board was then aware that the children of the 1950's came to school with a

better background of information than earlier generations-and that a primary

reason for this was exposure to new experiences via television in the home. This

situation suggested a need for curriculum changes to avoid trying to teach

children things they already knew. It also suggested that television might be

even more valuable in the classroom than in the living room.

The

Board was unaware of it then, but a movement was underway to set up a project

which could explore the uses of television for instruction. Backing this project

was a joint committee formed by the Electronic Industries Association and the

Ford Foundation's Fund for the Advancement of Education, with a number of

consultants representing various educational agencies. The committee wanted to

start a large-scale project-something that would provide a comprehensive test of

television. The emphasis was to be on regular, direct instruction by television

rather than on occasional or supplemental uses of it.

Washington

County was ultimately chosen as the site of this project on the basis of a

proposal to use television for instruction at all grade levels and in basic

subject areas; to use it for teacher education and for improvement and

enrichment of the curriculum. The county also proposed to test television's

usefulness in relieving classroom and teacher shortages and in achieving better

use of community and school resources. And finally, it proposed to find out

whether instruction by television was economical.

This

study, the Washington County Closed-Circuit Educational Television Project, was

an exploratory and practical experience - not a formal research experiment. It

extended over a period of five years, 1956-1961, and included the schools of an

entire county school system. The project program developed as a natural

outgrowth of the curriculum improvement program which had been evolving over a

period of many years. Television lessons were scheduled regularly to make them

integral parts of courses, but at no grade level did they occupy a major portion of a school day. The telecasts did not prevent pupils from having

personal contacts with teachers and from engaging in the give and take of

classroom discussions. The television experience was planned as only part of a

total learning experience for the pupil.

The

project got underway in the summer of 1956. One hundred teachers,

principals, supervisors and community leaders gathered at a workshop in July

and August to plan the new television instruction program. At the same time a

team of Chesapeake and Potomac Telephone Company engineers under William C.

Warman began stringing cable for the television network; and John R. Brugger

left his post as chief radio and television engineer at the University of

Illinois to design and install the transmission center. The installation was

completed that fall in time for telecasting to eight schools. The system was

expanded until by September 1963, every public school in the county was linked

to the television circuit.

As

the project developed, television came steadily into use at all grade levels and

in most subject areas. Television instruction was coordinated by staff

members T. Wilson Cahall and Robert F. Lesher. Each summer and at times during the school year, teachers, principals, parents, supervisors and

administrators gathered to assess progress and to restudy courses and teaching

methods. New courses were added, old ones altered -until today more than fifty

courses are included in the television program. By the time the project's

official life came to an end in 1961, the county not only had a new teaching aid

in the classroom, but also was well on the way toward having a vastly improved

curriculum and a new approach to teaching-by teams. The advantages of television

were apparent and the cost low enough so that after outside financing had ended,

the county was able to continue and even expand its use of television in the

classroom.

coordinated by staff

members T. Wilson Cahall and Robert F. Lesher. Each summer and at times during the school year, teachers, principals, parents, supervisors and

administrators gathered to assess progress and to restudy courses and teaching

methods. New courses were added, old ones altered -until today more than fifty

courses are included in the television program. By the time the project's

official life came to an end in 1961, the county not only had a new teaching aid

in the classroom, but also was well on the way toward having a vastly improved

curriculum and a new approach to teaching-by teams. The advantages of television

were apparent and the cost low enough so that after outside financing had ended,

the county was able to continue and even expand its use of television in the

classroom.

Throughout

the five years of the project, the county school system received support from

two major sponsors-the Electronic Industries Association and the Fund for the

Advancement of Education. Invaluable assistance also came from the Chesapeake

and Potomac Telephone Company of Maryland.

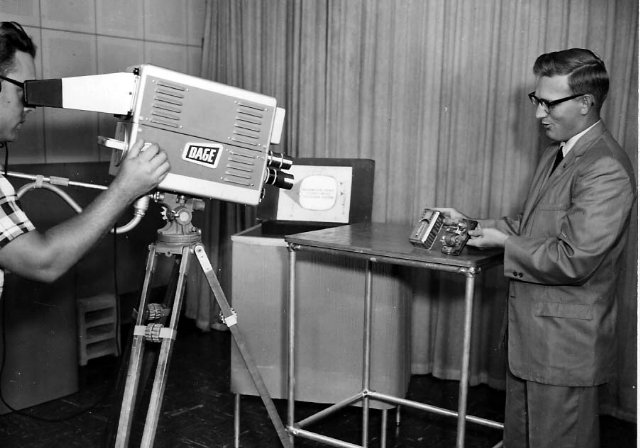

The

Electronic Industries Association, representing major electronics companies,

provided free of charge the necessary television cameras; receivers; and studio,

control room, projection and recording equipment. Seventy-five manufacturers

donated the equipment valued at $300,000.

The

Fund for the Advancement of Education and the Ford Foundation underwrote other

project expenses. These included the costs of designing the system,

administering and supervising the project, providing secretarial help, paying

cable rental fees, securing additional television sets, solving various

production problems, training technical personnel, and carrying out the

evaluation program. The Fund and the Foundation together contributed about

$200,000 a year to the project over the five-year period.

designing the system,

administering and supervising the project, providing secretarial help, paying

cable rental fees, securing additional television sets, solving various

production problems, training technical personnel, and carrying out the

evaluation program. The Fund and the Foundation together contributed about

$200,000 a year to the project over the five-year period.

The

Chesapeake and Potomac Telephone Company, with technical advice from Bell

Laboratories, developed the closed-circuit system for transmitting television to

the classroom. This system included more than 115 miles of coaxial cable plus

transmitting and amplifying equipment.

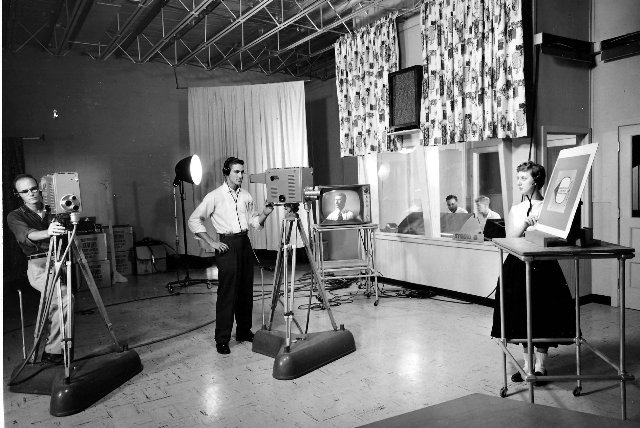

THE

SYSTEM AND THE STAFF

To

many educators, the most unfamiliar and perhaps worrisome aspect of classroom

television is the system itself. It is a complex electronic affair, with strange

devices and odd terms like "videcon," "zoom" and

"dolly out." Yet the actual task of operating such a system is not as

forbidding as it might sound. Washington County has found that it can operate an

extensive closed-circuit system with a minimum of professional and technical

assistance. Many other school systems are probably in a position to do the same.

In

the completed system in Washington County, forty-five schools are linked by

coaxial cable to form a closed-circuit television network. Six lessons can be

sent simultaneously over this cable and picked up on more than 800 standard

twenty-one-inch television sets in classrooms, school cafeterias and

auditoriums throughout the county. Many classrooms are equipped with two sets,

so that no pupil has to sit far from the screen. Auditoriums and other large

viewing rooms are equipped with several sets, generally one for every

twenty-five children. Large screens are now being used to replace small

receiving sets in auditoriums and other large viewing areas

The

lessons are transmitted from a Television Center adjacent to the Board of

Education offices in Hagerstown. This center is a pre-fabricated metal building

with a concrete block addition covering an area of 100 by 125 feet. A few years

ago it had a dirt floor and housed farm equipment. Now it contains five

television studios. Three of these are twenty-five by thirty feet, and two are

forty feet square-large enough to permit the use of an automobile or truck for

demonstrations. From these studios more than twenty-five lessons a day or 125

a week are transmitted to schools. These lessons are for the most part live

telecasts. The Columbia Broadcasting System, operating day and night seven

days a week, produces about 140 live programs, while National Broadcasting

Corporation in the same period transmits about sixty.

metal building

with a concrete block addition covering an area of 100 by 125 feet. A few years

ago it had a dirt floor and housed farm equipment. Now it contains five

television studios. Three of these are twenty-five by thirty feet, and two are

forty feet square-large enough to permit the use of an automobile or truck for

demonstrations. From these studios more than twenty-five lessons a day or 125

a week are transmitted to schools. These lessons are for the most part live

telecasts. The Columbia Broadcasting System, operating day and night seven

days a week, produces about 140 live programs, while National Broadcasting

Corporation in the same period transmits about sixty.

The

center also contains offices for production, engineering, supervisory and

clerical personnel, and a film projection room. Slides and films are stored,

repaired and previewed in the film room from which they can be fed either into

any of the five studios or directly to the schools over the closed-circuit

system. Adjacent to the Television Center is another pre-fabricated metal

building 100 by 40 feet, which contains office space for the studio teachers,

plus a workroom for the art staff.

Before

installing a television system for classroom instruction, it is first necessary

to

decide whether it shall be a closed- or open-circuit system. The open-circuit

system requires no cable, thus eliminating cable rental costs. But this system

provides a single transmission channel, so that only one lesson can be telecast

at a time. The closed-circuit system permits transmitting six or more lessons at

a time and since Washington County wanted to make extensive use of television

for teaching, it chose the closed circuit system.

At

the time the Board of Education asked the Chesapeake and Potomac Telephone

Company to install this system, in June of 1956, there was considerable question

as to whether it could be done economically. One engineer, for example, made a

guess that cable rental costs for such a system would amount to $2,500,000 a

year and capital costs to $7,000,000 or $8,000,000. His estimate made sense in

terms of costs then being experienced by the major networks; and there was no

other experience on which to base an estimate. No one had yet built an

economical closed-circuit system of the size and quality needed in Washington

County.

But

whereas the major networks transmit over a system combining expensive

underground cable and microwave relays, the Telephone Company ultimately

worked out for Washington County a system using a simplified coaxial cable. The

cable rental cost is about $150,000 a year, or one-seventeenth of the

$2,500,000 estimate. This made all the difference between a practical and an

impractical system. The completed network, in fact, represented an electronic

engineering milestone, and systems built since have been modeled upon it. The

Telephone Company used its Washington County experience to formulate the rate

schedule that is now being used nationwide for its closed-circuit service.

Company ultimately

worked out for Washington County a system using a simplified coaxial cable. The

cable rental cost is about $150,000 a year, or one-seventeenth of the

$2,500,000 estimate. This made all the difference between a practical and an

impractical system. The completed network, in fact, represented an electronic

engineering milestone, and systems built since have been modeled upon it. The

Telephone Company used its Washington County experience to formulate the rate

schedule that is now being used nationwide for its closed-circuit service.

The

television network first reached 6,000 pupils in 1956, then 12,000 in 1957,

16,500 in 1958, 18,000 in 1961, and 20,500 in 1963. The quality of the system

has been improved steadily, and while it is not without flaw, it is highly

reliable and generally excellent. The chief engineer estimates the system's

reliability at better than 99%, which means that breakdowns are extremely

rare.

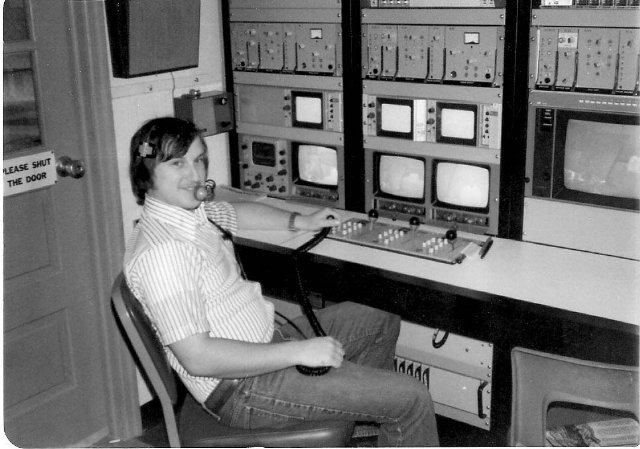

Operating

this system requires a substantial staff. A precise figure is hard to give

because there is no definite line between television personnel and

non-television personnel. In all, there are about seventy people working most

of the time in the television system-and this includes teachers, supervisors,

technical and clerical personnel, as follows:

-

Coordinator

1

-

-

Instructional

Supervisor 1

-

-

Teaching

Staff 25 (10 part-time)

-

-

Production

Staff 30 (17 part-time)

-

-

Engineering

Staff 8 (4 part-time)

-

-

Art

Staff 3

-

-

Clerical

Staff 4

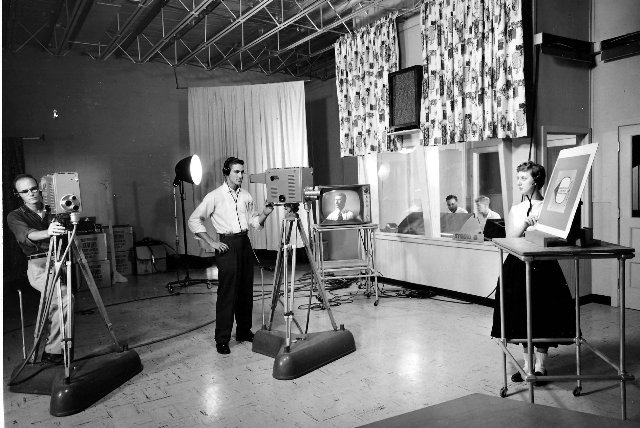

A

brief discussion of the duties of the coordinator and of the supervisory,

production, engineering and art staffs follows. While these departments are

discussed separately, in practice they work together very closely. The

standard studio crew for telecasting a lesson includes the teacher, two

technicians, a director, a floor manager and two cameramen. All are

interdependent.

COORDINATOR

The

coordinator works directly under the assistant superintendent in charge of

instruction as chief-of-staff for television. His duties induced coordination

of the work of the departments of engineering, production and instruction.

INSTRUCTIONAL

SUPERVISORY STAFF

A

supervisor of television instruction works as a member of the county staff of

general instructional supervisors. His responsibilities to the studio faculty

are similar to those of a principal in a conventional school. The entire group

of instructional supervisors, however, provides assistance to studio teachers in

the planning, teaching and evaluating of televised courses.

studio faculty

are similar to those of a principal in a conventional school. The entire group

of instructional supervisors, however, provides assistance to studio teachers in

the planning, teaching and evaluating of televised courses.

In

addition to their other relationships with studio teachers, instructional

supervisors arrange for them to meet with classroom teachers to discuss problems

of mutual concern as members of a teaching team.

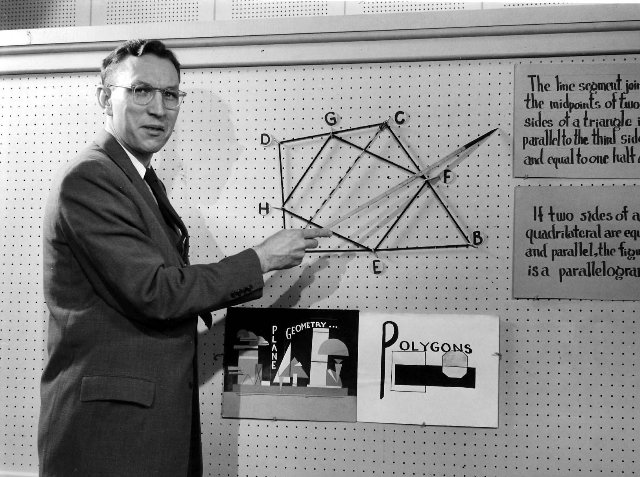

PRODUCTION

STAFF

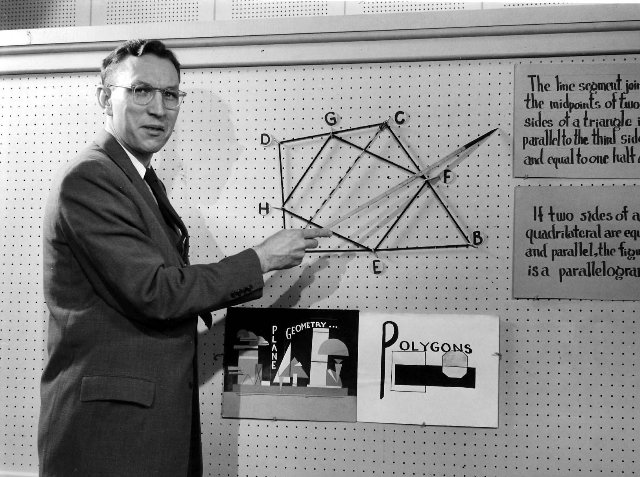

It

is the teacher's responsibility to present the lesson and the engineer's job

to transmit it, while it is the production staff's job to see that the lesson is

presented as effectively as possible. The task of the production staff is not

easily defined. The teacher is, essentially, the equivalent of the commercial

station's producer. He decides what his lesson is to include, and no techniques

of production are allowed to violate the teacher's conception of the method

and principles of teaching involved. The director is there to help the teacher

work effectively -to help him use television's many capabilities. Production

techniques are designed to implement the teacher's conception of the lesson.

The

teacher new to television has much to learn about teaching in a studio

situation. He must modify his habits of walking and talking. He must learn

the skills of interviewing, working with a studio crew, using studio cues and

signals and teaching with a variety of visual aids. This does not imply that the

television teacher must become a professional actor. It means mastering simple

techniques such as walking slowly enough for the camera to follow smoothly, and

gesturing in such a way that the camera does not distort the arm or hand. The

teacher must also learn how to prepare a script outline. The script is necessary

not only as a guide for the teacher but also as a cue to let the director know

what the teacher plans to do, and when. If the teacher intends to walk from one

part of the studio to another, the director must know when, so that he can have

the cameras in readiness. If films, slides or other kinds of visual aids are to

be used, the script must indicate to the director when and where in the sequence

of the lesson they are to come.

At

the Television Center, two experienced supervisors head the production staff.

They also teach communications courses for the Hagerstown Junior College. Most

of their staff of thirty is made up of junior college students, about half of

whom are majoring in communications. In addition to the two supervisors, there

are five full-time and three part-time directors. The rest of the staff is made

up of cameramen and floor managers who assist the director. The fact that many

of the students are studying communications at the junior college is a great

advantage in training them for work at the Television Center.

About

half of the production crewmen are new at the beginning of each school year.

Many of them arrive at the Television Center less than two weeks before school

opens, knowing only how to operate the family television set. In twelve days

they are operating cameras with considerable skill. Ninety per cent of the

television lessons are live. The rest are taped on occasions when the teacher

must be absent at the usual lesson time, wishes to interview a resource person

at his convenience or desires to evaluate his telecast as it is received in a

classroom situation.

weeks before school

opens, knowing only how to operate the family television set. In twelve days

they are operating cameras with considerable skill. Ninety per cent of the

television lessons are live. The rest are taped on occasions when the teacher

must be absent at the usual lesson time, wishes to interview a resource person

at his convenience or desires to evaluate his telecast as it is received in a

classroom situation.

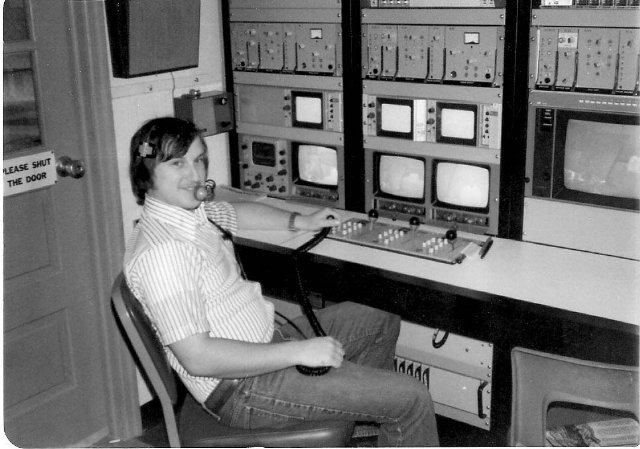

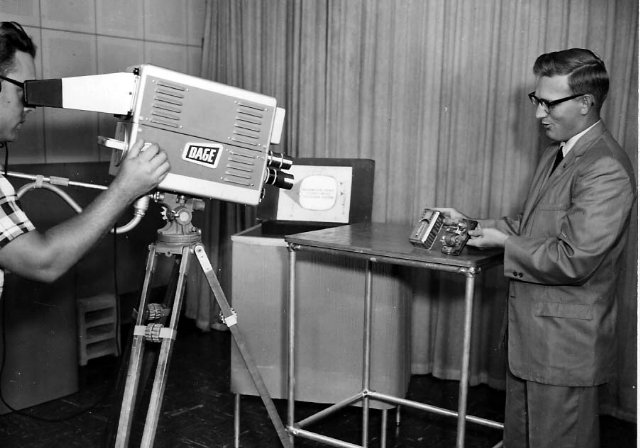

ENGINEERING

STAFF

The

Chesapeake and Potomac Telephone Company carries all responsibility for the

maintenance and operation of the cable and the system amplifying equipment.

All other equipment-television cameras, receivers, projection, recording, studio

and control room equipment-is the responsibility of the chief engineer and his

assistants. They maintain equipment and supervise the transmission of the

audio and video signals.

The

engineer and his assistant supervise the staff of technicians who have varied

responsibilities.

The

Engineering Department, like the Production Department, trains its own

personnel. With the exception of the chief engineer and his assistant, all are

junior college students or recent high school graduates. Not infrequently these

students go on to careers in electronics.

1.

The film room operator

-

maintains

a library of films which he catalogues, deans, splices, and inspects.

-

feeds

the proper film into the studio, or directly to the schools.

-

schedules

film previews for teachers and helps teachers select parts of a film for use

in their lessons.

2.

The video-tape recorder technician

-

records

lessons or special demonstrations

-

maintains

a library of approximately 200 one-hour tapes of previously recorded

materials

-

operates

the video-tape recorder

-

schedules

the replaying of topes

3.

The audio-video operators

-

connect

the studio to the proper channel

-

control

the equipment which determines the quality of the audio and video signal

-

operate

turn tables and recorders

4.

The maintenance crewmen

-

service

the 800 television sets located in 45 schools

-

test

the 15,000 tubes in the television system

-

install

and maintain equipment at the Television Center

ART

STAFF

The

Art Department provides a number of important services. There are three

full-time staff members in this department, all recent high school graduates

talented in art. They prepare most of the maps, charts, diagrams, acetate

overlays, special illustrations, models, and backgrounds for sets and similar

material used by the teachers in more than fifty televised courses. While much

commercially-produced illustrative material is available; often it is not

suitable for television. Many maps are too detailed, and illustrations are not

proportioned for the television screen, which requires a height /width ratio

of three to four. Worthwhile illustrative material can often be produced much

more cheaply than it can be purchased. Having the Art Department makes it

possible for teachers to be much more flexible in planning graphic materials

for their lessons-a vital advantage if the most effective use is to be made of

television.

TELEVISION

IN THE SCHOOLS

The

"correct" way to fit television into the conventional school routine

will probably be debated for years to come. The proper length of the television lesson, the optimum size for the television class opinions about

these and other problems may ultimately fill volumes. No one now has had enough

experience to know the best conclusions.

television lesson, the optimum size for the television class opinions about

these and other problems may ultimately fill volumes. No one now has had enough

experience to know the best conclusions.

Nevertheless,

a few things do seem clear. One is that television should not take up a major

portion of any pupil's school day; television is best used as a specialized kind

of learning experience or as an aid to classroom instruction. The other is that

a television lesson should generally be followed as soon as possible by a

session with the classroom teacher.

But

there is now no easy answer to the question of how long a television lesson

should be. The fact that the attention span of a first grader is shorter than

that of a high school pupil has bearing on the question. So does the fact that

pupils at the same grade level can profit by a longer television lesson in a

subject like art, than in others, such as conversational French, where more

concentration is required.

At

present elementary pupils spend 7.3 % to 13 % of their classroom time watching

television lessons. These lessons, ranging in length from thirteen to

twenty-five minutes, are followed by work in the subject with the classroom

teacher. Junior high school pupils spend almost one-third of their time in

television classes, while high school pupils seldom spend more than 10% of

their time in television classes.

None

of these time periods are recommended as the ideal. The staff is inclined to

believe that the amount of television viewing time in the elementary schools is

satisfactory. Junior high schools may have too much viewing time, while high

school pupils might profitably spend more time than they now do.

The

flexibility of the elementary school day makes it much easier to use

television there than in the junior or senior high school. Since there are no

rigidly defined periods in the elementary school, the classroom teacher can

devote as much or as little time as he deems necessary to preparation for the

television lesson, or to discussion and other follow-up work. The junior and

senior high school schedules, on the other hand, are relatively inflexible.

When the day is made up of six periods of equal length, both television and

classroom teachers are more limited in what they can do.

In

certain subjects, television is obviously very successful. In others, it is less

so, although it appears that in no subject does television fail to produce

results at least as good as those achieved when classroom instruction alone is

used. There are many on the county staff now who believe that any well taught

subject will be effective on television, and that failures are caused by

unsatisfactory presentation, not by weaknesses inherent in television. It is

certainly true that no one should judge hastily whether or not a course is

suitable for television. Many teachers in Washington County who thought that

arithmetic could not be taught successfully on television have changed their

minds, because test results have made it quite clear that elementary pupils made

much more rapid progress in arithmetic with television than they did without it.

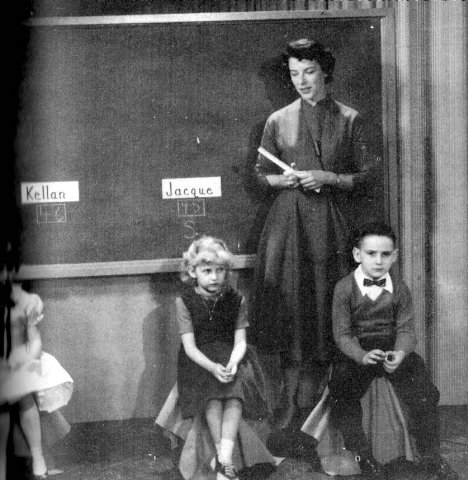

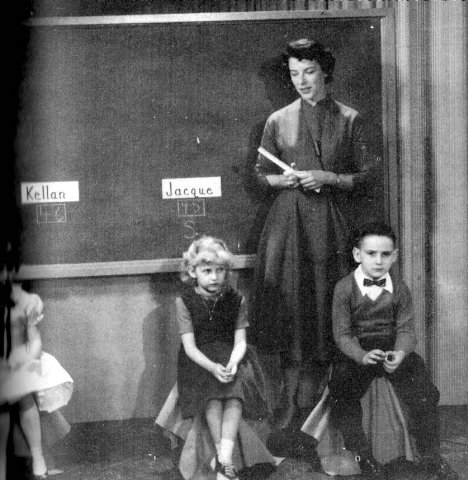

TEACHERS

AND TELEVISION

The

impact of television on the Washington County school system has been far

greater than anyone could have predicted in 1956. Nowhere has this impact been

more obvious than in the area of teaching and teaching methods.

Television

has made the talents of some' of the county's teachers far more widely available

than they were before. This benefits not only the pupils, but also many other

teachers who, for the first time, have an opportunity to watch their colleagues

at work. When this first happened, teachers with thirty years' experience

sometimes discovered, often to their surprise, that there were quite a few

teaching techniques they had not known about. Before television, these teachers

had to depend largely on theory and experience to guide them. Now they have a

daily opportunity to watch and weigh the methods and theories of others, and to

see how these work out in practice. For most teachers, this has been an

enlightening experience. It has provided on-the-job training never before

possible.

An

even more notable change brought by television has been the establishment of

teaching teams. The teacher in the studio and the teachers in the classroom

comprise the team.

Undoubtedly,

Television has a place in the instructional program of the school.Television

adds a new dimension to the instructional program. Through the use of visuals

and other techniques unique to television, classroom television provides

experiences for Washington County pupils that could not be achieved in other

ways.

The

Board of Education first considered using television in the schools in 1954.

The Board was then aware that the children of the 1950's came to school with a

better background of information than earlier generations-and that a primary

reason for this was exposure to new experiences via television in the home. This

situation suggested a need for curriculum changes to avoid trying to teach

children things they already knew. It also suggested that television might be

even more valuable in the classroom than in the living room.

The

Board of Education first considered using television in the schools in 1954.

The Board was then aware that the children of the 1950's came to school with a

better background of information than earlier generations-and that a primary

reason for this was exposure to new experiences via television in the home. This

situation suggested a need for curriculum changes to avoid trying to teach

children things they already knew. It also suggested that television might be

even more valuable in the classroom than in the living room. coordinated by staff

members T. Wilson Cahall and Robert F. Lesher. Each summer and at times during the school year, teachers, principals, parents, supervisors and

administrators gathered to assess progress and to restudy courses and teaching

methods. New courses were added, old ones altered -until today more than fifty

courses are included in the television program. By the time the project's

official life came to an end in 1961, the county not only had a new teaching aid

in the classroom, but also was well on the way toward having a vastly improved

curriculum and a new approach to teaching-by teams. The advantages of television

were apparent and the cost low enough so that after outside financing had ended,

the county was able to continue and even expand its use of television in the

classroom.

coordinated by staff

members T. Wilson Cahall and Robert F. Lesher. Each summer and at times during the school year, teachers, principals, parents, supervisors and

administrators gathered to assess progress and to restudy courses and teaching

methods. New courses were added, old ones altered -until today more than fifty

courses are included in the television program. By the time the project's

official life came to an end in 1961, the county not only had a new teaching aid

in the classroom, but also was well on the way toward having a vastly improved

curriculum and a new approach to teaching-by teams. The advantages of television

were apparent and the cost low enough so that after outside financing had ended,

the county was able to continue and even expand its use of television in the

classroom. designing the system,

administering and supervising the project, providing secretarial help, paying

cable rental fees, securing additional television sets, solving various

production problems, training technical personnel, and carrying out the

evaluation program. The Fund and the Foundation together contributed about

$200,000 a year to the project over the five-year period.

designing the system,

administering and supervising the project, providing secretarial help, paying

cable rental fees, securing additional television sets, solving various

production problems, training technical personnel, and carrying out the

evaluation program. The Fund and the Foundation together contributed about

$200,000 a year to the project over the five-year period. metal building

with a concrete block addition covering an area of 100 by 125 feet. A few years

ago it had a dirt floor and housed farm equipment. Now it contains five

television studios. Three of these are twenty-five by thirty feet, and two are

forty feet square-large enough to permit the use of an automobile or truck for

demonstrations. From these studios more than twenty-five lessons a day or 125

a week are transmitted to schools. These lessons are for the most part live

telecasts. The Columbia Broadcasting System, operating day and night seven

days a week, produces about 140 live programs, while National Broadcasting

Corporation in the same period transmits about sixty.

metal building

with a concrete block addition covering an area of 100 by 125 feet. A few years

ago it had a dirt floor and housed farm equipment. Now it contains five

television studios. Three of these are twenty-five by thirty feet, and two are

forty feet square-large enough to permit the use of an automobile or truck for

demonstrations. From these studios more than twenty-five lessons a day or 125

a week are transmitted to schools. These lessons are for the most part live

telecasts. The Columbia Broadcasting System, operating day and night seven

days a week, produces about 140 live programs, while National Broadcasting

Corporation in the same period transmits about sixty. Company ultimately

worked out for Washington County a system using a simplified coaxial cable. The

cable rental cost is about $150,000 a year, or one-seventeenth of the

$2,500,000 estimate. This made all the difference between a practical and an

impractical system. The completed network, in fact, represented an electronic

engineering milestone, and systems built since have been modeled upon it. The

Telephone Company used its Washington County experience to formulate the rate

schedule that is now being used nationwide for its closed-circuit service.

Company ultimately

worked out for Washington County a system using a simplified coaxial cable. The

cable rental cost is about $150,000 a year, or one-seventeenth of the

$2,500,000 estimate. This made all the difference between a practical and an

impractical system. The completed network, in fact, represented an electronic

engineering milestone, and systems built since have been modeled upon it. The

Telephone Company used its Washington County experience to formulate the rate

schedule that is now being used nationwide for its closed-circuit service.

studio faculty

are similar to those of a principal in a conventional school. The entire group

of instructional supervisors, however, provides assistance to studio teachers in

the planning, teaching and evaluating of televised courses.

studio faculty

are similar to those of a principal in a conventional school. The entire group

of instructional supervisors, however, provides assistance to studio teachers in

the planning, teaching and evaluating of televised courses. weeks before school

opens, knowing only how to operate the family television set. In twelve days

they are operating cameras with considerable skill. Ninety per cent of the

television lessons are live. The rest are taped on occasions when the teacher

must be absent at the usual lesson time, wishes to interview a resource person

at his convenience or desires to evaluate his telecast as it is received in a

classroom situation.

weeks before school

opens, knowing only how to operate the family television set. In twelve days

they are operating cameras with considerable skill. Ninety per cent of the

television lessons are live. The rest are taped on occasions when the teacher

must be absent at the usual lesson time, wishes to interview a resource person

at his convenience or desires to evaluate his telecast as it is received in a

classroom situation.

television lesson, the optimum size for the television class opinions about

these and other problems may ultimately fill volumes. No one now has had enough

experience to know the best conclusions.

television lesson, the optimum size for the television class opinions about

these and other problems may ultimately fill volumes. No one now has had enough

experience to know the best conclusions.